Fear is stifling potential use of robots in UK care homes, says AI researcher

There is considerable stigma around the use of robots in care homes, and in the UK “we have already decided without any evidence that we don’t like the use of robotics in care,” according to a leading AI researcher.

Chris Papadopoulos, who is leading the biggest trial in the world into the use of AI (artificial intelligence) in care homes, spoke at the recent Future of Care conference, saying “we shouldn’t be frightened of the potential of robotics in care”, and blamed the media for creating a stigma and deciding what we value.

In Japan, it is a very different story and the concept of social care robotics is much more accepted. A quarter of Japanese people are over 65, and with a shortfall of care workers and an antipathy to immigration, the government there has invested considerable funding into care robots, with a Tokyo care home now using 20 different robots.

A Japanese company has even gone as far as creating a nursing-care robot called Robobear that can lift patients from their beds into wheelchairs and help them to stand up.

The same shortfall of care workers is evident in the UK and the research project led by Dr Papadopoulos, a public health lecturer at Bedfordshire University, is exploring the use of robots in UK care homes run by Advinia Health Care, as well as the HISUISUI home in Japan.

'It isn’t about replacing jobs, it is about complementing existing care'

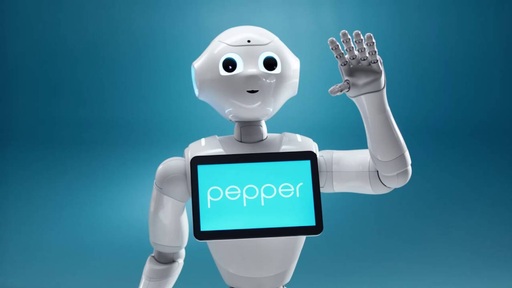

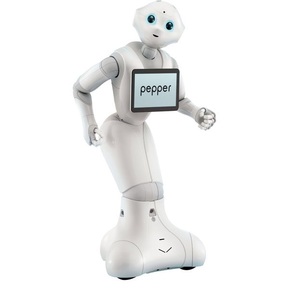

The CARESSES project which is funded by the EU and the Japanese government, is designed to develop a robot that will adapt to a person’s cultural identity. It uses existing robots, such as the humanoid robots called Pepper produced by SoftBank Robotics.

The aim is for the robots to interact with residents and learn about them by taking into account their cultural identity and individual characteristics. They can remind residents to follow the therapy prescribed to them, encourage them to have an active lifestyle, help them stay in touch with family and friends, suggest appropriate clothing for specific occasions and remind them about upcoming birthdays or religious holidays, according to the project.

CARESSES robots are complementary to care home workers, states the project which adds ‘they do not replace them, but they help make the lives of the people they assist less lonely and they make it less urgent for care home workers to be near’.

Dr Papadopoulos says: “Taking into consideration a person’s cultural background is an absolute pillar of care. When robots are culturally competent, they will produce better patient outcomes.

“Therefore it is imperative we test whether robotic cultural competence has potential.”

Artificial intelligence can promote independence and quality of life'

Dr Sanjeev Kanoria, chairman of Advinia Health Care, who is also a liver surgeon, agrees with Dr Papadopoulos that “robots will not replace care workers”

“Robots will not replace care workers but such innovation could streamline processes such as medication delivery, setting reminders and providing access to technology and entertainment. This technology will not only improve care delivery, but also promote independent living and quality of life. Particularly for dementia patients, agitation can be reduced by offering culturally-appropriate care support.”

He added: “The robots do not have limbs, so they cannot carry out essential care tasks but they have artificial intelligence which allows them to learn about the patients and residents and communicate this learning to the care workers enabling them to do their task better.”

Dr Papadopoulos is all for taking things slowly. He says: “Before we can go ahead with robotics, we need more research. We need to look at whether it makes an impact, to what degree it is effective and not assume one size fits all.

“So far all the studies show indicate improved wellbeing.”

When the project was first announced last year, some charities and organisations criticised the concept, with Judy Downey from the Relatives and Residents Association saying the key to looking after someone “is having a relationship” with them, adding that what matters “is the smile, the human touch”.

Disability charity Scope dismissed 'pipe dreams of robot carers' and Unison said robots are “essentially sticking plasters masking a much bigger problem”.

However Dr Papadopoulos is keen to reiterate “it isn’t about replacing jobs, it is about complementing existing care.”

He adds: “We need to embrace ethics so even if it enhances patients’ outcomes, we need to look at whether it reduces staff morale.

“We have to take the ethical approach. Even if enough of the outcomes show robots are reducing falls and people’s use of medication, but people are losing their jobs, we would need to think again.”

But he also doesn’t believe robots should just be consigned to carry out monotonous tasks, saying “they shouldn’t just be doing mundane tasks. As long as it doesn’t replace care staff interacting with residents.”

He sees them as being able to communicate with residents asking them how they are feeling and what music they would like to listen to or what films they would like to watch.

He says: “We do need to keep an eye on the ethics of AI in care homes. There is no need to rush this and rush widespread implementation.

“We need to have a conversation about what we want. Of course we don’t want a future where everything is delivered by robots.

“In surgery we already have robots doing things that humans can’t do as well. Yet people say robots cannot care as it is all about compassionate touch. Let’s not be frightened by this potential."

For more information about the CARESS project, go to www.caressesrobot.org

Latest Features News

28-Nov-19

2019 Election: Labour pledges £10.8 bn for free personal care while Boris Johnson sidelines social care

28-Nov-19

2019 Election: Labour pledges £10.8 bn for free personal care while Boris Johnson sidelines social care

18-Oct-19

Podcast: Wendy Mitchell and dementia: 'My biggest fear is not knowing who my daughters are'

18-Oct-19

Podcast: Wendy Mitchell and dementia: 'My biggest fear is not knowing who my daughters are'

30-Sep-19

World's oldest diver aged 96 says 'never accept the fact you are getting old'

30-Sep-19

World's oldest diver aged 96 says 'never accept the fact you are getting old'

27-Sep-19

Exclusive: Care minister backs care workers' call for time off to grieve and attend funerals

27-Sep-19

Exclusive: Care minister backs care workers' call for time off to grieve and attend funerals

20-Sep-19

Podcast: Gyles Brandreth urges care workers to learn poetry with elderly

20-Sep-19

Podcast: Gyles Brandreth urges care workers to learn poetry with elderly