Exclusive: Care minister backs care workers' call for time off to grieve and attend funerals

Care workers have confessed to feeling devastated and struggle to cope after the death of someone they have cared for and in response to staff experiences shared by carehome.co.uk, care minister Caroline Dinenage is calling on care providers to give employees time off to grieve and attend funerals.

Care minister Caroline Dinenage has told carehome.co.uk: “Care workers do an amazing and essential job supporting some of society’s most vulnerable, and can develop close bonds with the people they care for.

“Their own wellbeing is no less important and employers should recognise that workers may need time and support with their grief if someone in their care passes away.

“Providing this kind of support is key to retaining talent and ensuring we have a workforce fit for the future.”

The Department of Health and Social Care said recognising that care workers need support to manage their grief is also embedded in the ‘Retaining your staff - using a values-based approach’ key cards offered by Skills for Care for employers which were launched this year.

‘Devastated’

Death may be a regular, if unwelcome, visitor entering care homes across the country but care staff have revealed how managers respond can spell the difference between good care at a setting and a ‘don’t care’ culture.

Dealing with death is part of the job but if you spend a lot of your time with someone and they die, the sense of loss can be profound. Shock, overwhelming sadness, exhaustion, anger and guilt can be felt after a death. Mental health issues can also be triggered, if a death is followed by poor support.

Joanna*, (name changed to protect anonymity*) worked at a care home for people with learning disabilities and says she felt "extremely devastated" when two people she cared for died.

“I was very shocked and did not know how to deal with the emotions. I repressed my own feelings to the point where even a couple of years later I still haven’t been able to fully experience and explore them.”

April, aged 42, had a severe learning disability and Joanna remembers how she “loved going out shopping and buying anything pink”.

“April had the most beautiful smile and I really liked her confidence and independence." Recalling a deep attachment to her, she says: “I personally learned a lot from her. April taught me that it was ok to be myself at least sometimes.”

’I learned of her death via voicemail’

April’s life ended when she was taken to hospital following a 999 call. Her death in hospital “was very unexpected”.

“We later found out she had cancer. The manager did not inform me of April’s death - I learned of her death via a voicemail from another support worker.”

The care worker also feels the pain of losing Libby - a 38-year-old woman with a severe learning disability. Though she could not talk, Libby loved music, ”was very tactile and loved to hold hands”.

Libby died in hospital of organ failure caused by sepsis.

“I was with Libby when she died. I mainly felt anger, that they both had such a painful, undignified and unnecessary death”.

Without “proper guidance” from her manager and access to a counsellor, she believes the utter sadness she felt intensified, which led to her leaving the care sector altogether.

“I still feel incredibly sad by their deaths and believe that this and the consequential lack of support has significantly negatively impacted my mental health.

“I also truly believe that this has contributed to my current ill health status which means I am not able to work.”

Joanna wants other care workers to have regular discussions about death and end of life care in team meetings, 1 to 1 meetings with management involving open conversations about death, team training and access to bereavement counselling.

‘They didn’t even ask me if I wanted to go to the funeral’

Care workers, like everyone else, experience grief in different ways.

“I still dream about the lady… Sophie” says care worker Karolina Gerlich, who is also chief executive of National Association of Care And Support workers (NACAS).

“After Sophie died, it was a good few weeks before I felt like I didn’t have a bad feeling in my stomach."

Sophie was 97-years-old and had dementia. “She was a proper, old English lady. We used to polish silver together on Saturdays. She had tea and cake at 4.30pm every afternoon”.

As a live-in care worker, “I was caring for her for seven months…living her life. We did everything. Like a small family.

“People who have never done social care very often talk about strict personal boundaries. It’s impossible to maintain a ‘strictly professional’ stance.”

The care worker recalls the shock of going on holiday and returning to discover Sophie had died. “I was upset. They didn’t let me know. They didn’t even ask me if I wanted to go to the funeral. They fixed the rota so I had to do care work for someone else.

“I said to them ‘I need time off’ and I asked if someone could cover for the day and they said no. There was no interest and no cooperation from them to help.

"I’ve experienced this multiple times. I know other care workers who are not given time off by employers to attend funerals."

Ms Gerlich no longer provides live-in care. The experience she describes occurred with a previous employer.

She now works as a home care worker and as the chief executive of NACAS she says “Care providers should have an open conversation with staff and see how care workers can be supported better. If I’d had the option of a few days off I would have taken it.”

Bottled up emotions have ‘all got to go somewhere’

A grieving care worker may look like they are working but their mind is not on the job. While staff rotas continue ‘business as usual’ becomes a dirty word for the grief-stricken.

A bottling-up of unspoken emotions, as care home manager Mark Topps explains, “has all got to go somewhere”. As the manager of Little Wakering House in Southend-on-Sea, a care home for people with mental health issues, he says he is keen to tackle care worker bereavement head on.

He gives staff a chance to talk and share happy memories, “so that they can get it off their chest”. I have a very open-door policy, staff know they can contact me 24/7.

“Even if they ring me at two in the morning, I always say to them I’d rather you talk to me about what’s going on, as opposed to bottling it up.”

Mr Topps opens a memory book to give staff the chance to jot down happy memories which they share and laugh about with colleagues making “everyone feel happier”.

He is appalled some care workers are not given time off to grieve or attend funerals and has even told another care home manager he should have let his employee leave work to go to a funeral. He believes such uncaring practices must change, as it inevitably “impacts on the quality of care”.

“Those feelings have got to go somewhere and if you are grieving it can turn to anger. That anger’s got to go somewhere and it’s probably going to go on the people that we’re looking after.

“I’d probably say to them ‘If you want to go home you can’. We’d probably make it a paid day as opposed to them having unpaid leave. I think sometimes carers are waiting for managers to give that reassurance that it’s alright to do something.”

Karen Brennan, founder of Self Care for Carers, can give 'whole team' staff training in bereavement and wellbeing in care homes. She warns “unacknowledged grief causes problems that can go on for years”.

She recommends an ‘after death’ debrief session which gives staff time to reminisce about the person. The debrief must also involve the manager acknowledging sensitively the loss, “giving space to people’s feelings” and taking time to pause to celebrate the person's life. They should also ask staff what support they can offer and say ‘thank you’ for the care they gave the person who died.

Latest Features News

28-Nov-19

2019 Election: Labour pledges £10.8 bn for free personal care while Boris Johnson sidelines social care

28-Nov-19

2019 Election: Labour pledges £10.8 bn for free personal care while Boris Johnson sidelines social care

18-Oct-19

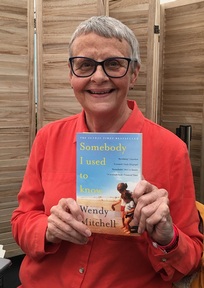

Podcast: Wendy Mitchell and dementia: 'My biggest fear is not knowing who my daughters are'

18-Oct-19

Podcast: Wendy Mitchell and dementia: 'My biggest fear is not knowing who my daughters are'

30-Sep-19

World's oldest diver aged 96 says 'never accept the fact you are getting old'

30-Sep-19

World's oldest diver aged 96 says 'never accept the fact you are getting old'

27-Sep-19

Exclusive: Care minister backs care workers' call for time off to grieve and attend funerals

27-Sep-19

Exclusive: Care minister backs care workers' call for time off to grieve and attend funerals

20-Sep-19

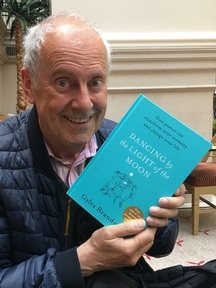

Podcast: Gyles Brandreth urges care workers to learn poetry with elderly

20-Sep-19

Podcast: Gyles Brandreth urges care workers to learn poetry with elderly