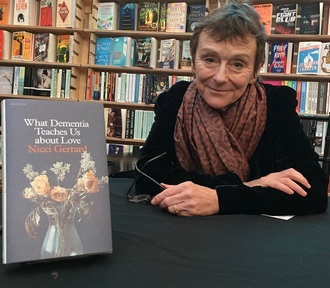

'Guilt' and 'stigma' surrounds this 'invisible illness' - Nicci Gerrard speaks openly about dementia

Nicci Gerrard, best-selling author of What Dementia Teaches Us about Love, says dementia teaches you to value "time" and "vulnerability".

Ms Gerrard's father Dr John Gerrard lived with Alzheimer’s for 10 years and was happily living at home with his wife. Then her father was admitted to hospital for five weeks with leg ulcers.

Ms Gerrard, speaking at the Cheltenham Literature Festival, revealed: “An outbreak of norovirus meant we weren’t allowed to visit." Ms Gerrard believes his isolation from his friends and family made his dementia worse. She said: "He went off a cliff in terms of wellbeing.

"We weren’t there to help him hydrate, help him eat, keep him connected to the world, hold his hand or to show him he was loved. It was that sense of how precarious the human mind is. Once you have dementia, life is precarious. He was a ghost in the last nine months before he died.”

After the death of her father in November 2014, Ms Gerrard became a co-founder of John's Campaign. The aim of the campaign is to give the carers of those living with dementia the right to stay with them in hospital, in the same way, parents stay with their sick children. This is now recognised by the NHS and almost every hospital across the UK has signed up.

'Carers should be welcome in hospitals at all times’

She said: “It is an absolute nonsense carers are kept away from people they love and look after.

"One of the reasons why I wrote my book is that there were lots of things I didn’t know about until it was too late to know about them so the obvious example is the fact carers should be welcome in hospitals at all times.”

Ms Gerrard believes correcting people when they have dementia is “very cruel”. She said: “To say to people no it’s not Monday, it’s Wednesday, is insensitive.”

The year before her father’s death, Dr Gerrard went to Sweden with Ms Gerrard and her husband, best-selling author Sean French for a family holiday. She said: “He was very happy picking wild mushrooms and having crayfish parties. He had swum in a lake and we had put him to bed.

“It was 11:30 in the evening and we were both tired out sitting there with a glass of wine when my father appeared. He had got dressed again and he said, ‘I think it’s time for our supper now’. The easiest thing to say would have been to say, ‘look it’s midnight, back to bed’ but we just said, ‘It is.’ and we just made a really nice meal and we had a midnight feast.

“When I think of that, I want to weep with gratitude we didn’t send him back to bed because it was lovely, and you don’t lose those memories.”

In her book, Ms Gerrard talks about how dementia is not so much a stigma compared to when she was a child.

‘We are the first generation to have really considered it mindfully. When I was a child, it was scarcely visible and rarely acknowledged. My grandfather on my mother’s side of the family had dementia. Although I was aware of this, it was only in a muted way: they became like figures who had once been vivid in my life but were now being gradually rubbed out.’

'This is a very invisible illness, it happens out of sight'

Speaking of her father, Ms Gerrard told the Cheltenham audience: “My father was very proud of being a doctor. He was very proud of his competence and a good carer of other people. He was practical and competent.

"When he got his diagnosis of dementia, he couldn’t speak about it he wouldn’t say something is wrong and made it immensely more complicated for everyone around him to deal with it.

“We’re scared of it because it’s about decaying and endings. Dying is about what we do, but we don’t talk about what we do. It’s about all those things we want to hide away and because we don’t want to see what is going on. One of the many problems is this is a very invisible illness; it happens out of sight and there is a stigma attached to it.

"I feel so guilty. When I look back all through my young adulthood up until when my father got ill, I started noticing it. I think I was just in a rush; I was on this narrow road of things I had to get done. The thing is we are all vulnerable in the end."

Ms Gerrard believes poetry and music can have an huge impact on people. “The last time my children saw my father, he had spent the last nine months of his life lying in a hospital bed. He couldn’t speak a syllable; he couldn’t lift his head up.

“He used to love poetry and he used to read poems to us. I made an anthology of poems and we read out one of the poems my father. While we were chanting this, my father who could say nothing joined in.

"He knew the words somewhere in his deep grooves of the self had been covered up by the wreckage. He was still there. It was a moment of extraordinary connection but also really a quick reminder nobody has gone.

“Time is our great enemy. We value success and purpose and efficiency, and we don’t value things like having time, listening. We don’t value vulnerability and we don’t value being at each other’s mercy.”

Latest News

29-Jul-24

Dementia Bus gives carehome.co.uk staff insight into life with dementia

29-Jul-24

Dementia Bus gives carehome.co.uk staff insight into life with dementia

27-Jul-23

UK's top home care agencies in 2023 revealed

27-Jul-23

UK's top home care agencies in 2023 revealed

30-Nov-22

A quarter of older people keep their falls secret from family

30-Nov-22

A quarter of older people keep their falls secret from family

29-Nov-22

'Covid-19 has not gone away' say terminally ill

29-Nov-22

'Covid-19 has not gone away' say terminally ill

28-Nov-22

IT consultant who received poor care opens 'compassionate' home care business

28-Nov-22

IT consultant who received poor care opens 'compassionate' home care business